History

-

A special vinegar

-

The House of Este and Balsamic

-

Why “balsamic”?

-

The Consorteria

We can assume that in ancient times people collected wild fruits that were ripe and sweet; when squeezed, the juice was sweet and pleasant, but once it fermented, naturally it turned to alcohol and was even more delectable and intoxicating. Just as naturally, any leftovers turned sour and it was soon discovered that vinegar could be used to preserve food: this very quickly led to deliberate production of vinegar, with far-reaching consequences on people’s way of life that undoubtedly shaped their future. Having a steady, practically spontaneous production of vinegar, which made it possible to preserve food, was a decisive factor in man’s evolution from hunter-gatherer to farmer and, ultimately, his choice to settle in an easily defensible territory. Since time immemorial, vinegar has been used to preserve and disinfect, but also for its thirst-quenching, tonic and digestive properties, through to its use in cooking. There is no documented evidence of this, but it was nature itself that determined these transformations, which were inevitable at that time, so it is easy to see how vinegar production evolved, enabling advances in society itself. It is no coincidence that the first evidence of the use of vinegar dates back to the great ancient Egyptian civilization, over 10,000 years ago, but it was also used by the Persians and Babylonians to preserve food. The rise of great civilisations continued to be followed by the use of vinegar, as already occurred in the third century BC in Greece and later during the Roman Empire. These were civilisations in pursuit of expansion, conquerors with mighty armies to be fed in all seasons, and preserving food was of paramount importance.

A special vinegar

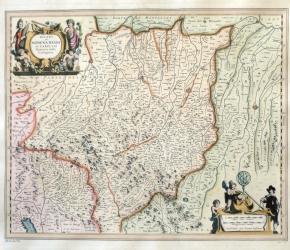

From Ancient Roman times on, however, written references also mention a special product, a different type of vinegar with exceptional aromas and taste which was produced in the area corresponding to the modern-day provinces of Modena and Reggio Emilia.

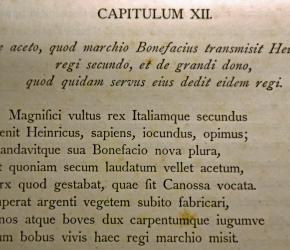

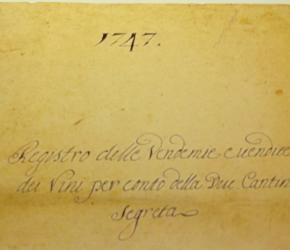

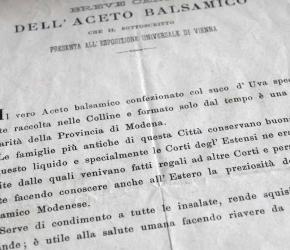

The earliest mention of this vinegar using the term “balsamic” appears in a document only in 1747, in the “Register of grape harvests and wine sales of the secret Ducal cellars”. What was this product and how did it come about? And why does today’s market offer two different types of Balsamic Vinegar, obtained from different production processes? Even in ancient times, there was extensive grape production across this area, the variety that thrived here being the wild “Vitis Labrusca” vine. A reasonable hypothesis is that the Romans conquered the area, driving away the Etruscans, precisely to establish grape production here. Cicero described how the wine produced was excellent, but had to be drunk while still young, as it did not age well. So while, on the one hand, the wine did not lend itself to ageing and was less than ideal for selling, on the other hand the grape juice was extremely interesting because, when concentrated, it was much sought after as a sweetener. Depending on the use, grape must could be reduced down to three levels of concentration. It was classified as Caroenum when 30% concentrated, Defrutum for 50% and Sapa when reduced to a third its original volume, although the three levels could also refer to different recipes, as can be evinced from the countless contradictions in ancient texts. In his “De Rustica”, Lucius Junius Moderatus Columella, who lived from 4 to 70 AD, describes the characteristics of the cooked must produced in the area corresponding to the modern-day provinces of Modena and Reggio Emilia, noting that the sweet and sour liquid had the tendency to spoil and turn sour. Thus, for a perfect, dense product, Columella recommends reducing the grape must by at least one third of its original volume. He describes the use of cooked must as an additive for wines and vinegars and as a sweetener in place of honey, which then - as now - was very expensive. Pliny the Elder confirmed in his “Naturalis Historia” how Sapa and Defrutum were produced as substitutes for honey, which was rarer and more expensive, or for making sauces with other ingredients. This was therefore something new, a cooked and concentrated grape must that could sometimes turn sour, or was deliberately soured, made right here in this area which was renowned for its large-scale grape production. Skip forward a few hundred years or so, and in the very same area a monk called Donizone, in “De Vita Mathildis” (1111-1116 AD) describes an episode that occurred in 1046 involving Henry II of Franconia, (a kingdom encompassing all of central Europe, including northern Italy) who sent a request to the marquis Boniface of Canossa for a bottle of “that highly praised vinegar which was said to be perfect”. The marquis of Canossa summoned his artists and set them to work immediately on a silver sculpture; the cart drawn by oxen produced by the silversmiths was then laden with a precious bottle of the marquis’s vinegar and sent as a gift to the king, who “was greatly impressed by the magnificent gift”. Henry II was travelling to Rome to be crowned Holy Roman Emperor by the Pope, a circumstance that made it even more important that the gift be of remarkable significance. The monk Donizone’s writing is the first document alluding to the presence, in the area corresponding to the modern-day provinces of Modena and Reggio Emilia, of a vinegar of such exceptional quality as to constitute a fitting gift for a king!

The House of Este and Balsamic

From the 16th century on, Balsamic Vinegar’s destiny was inextricably linked to the history of the House of Este. An anonymous volume housed in the Estense Library in Modena, titled “La Grassa. Libro de Boletini” (1556), details how the ducal pantries were stocked with vinegars classified according to different levels of quality suited to different uses: “agresto”, “comune”, “comune per la bocca”, “da tavolo”, “da campagna”, “per cucina”, “per gentilhomini” (unripe, common, common for the mouth, for the table, rustic, for cooking, for gentlemen). The city archives provide ample documentation of a bustle of activity surrounding the production of a singular, extraordinary vinegar which was the culmination of the Modenese population’s deep-rooted and genuine vocation for vinegar-making. This vinegar’s fame spread rapidly, fuelled also by the intrigue that cloaked its preparation. There is no doubt that this wonderful liquid, every bit as mysterious as it was delicious, had cast its spell over the Este Court: on moving to Modena, the royal household immediately extolled the virtues of the elixir and, in later centuries, granted Balsamic an “aristocratic patent”. Francesco I d’Este (1629 – 1658), Duke of Modena, took a special interest in the production of this vinegar and during the construction of the Ducal Palace he had a vinegar loft installed in the tower known as “Torre del Prato”. In 1638, amid great pomp and splendour, Francesco I travelled to Madrid to the court of Philip IV, King of Spain, taking with him a carriage laden with gifts, among which were numerous bottles of hundred-year-old Balsamic Vinegar. He also gifted a bottle to the artist Diego Velázquez, who had been commissioned to paint the Duke’s portrait. Since, given its exceptional quality, the Duke regularly gifted this vinegar to fellow European royals, often in quantities that far exceeded his own production capabilities, the aristocratic families nearest to him were duty-bound to keep him supplied with the noble product. In 1764, to mark the visit to the Duchy by the Grand Chancellor of Muscovy, Count Michele Woronzow, Duke Francesco III gifted him “a crateful of bottles of the Court’s Balsamic Vinegar”. The Count was so enamoured of the fragrant condiment, he requested further provisions for his own family and for the Empress, Catherine the Great. Duke Ercole III d’Este also celebrated the coronation of Archduke Francis of Austria as Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation in 1792 by sending an ampoule of vinegar as a gift to mark the milestone ceremony. Once again, the inestimable value of the product, coupled with the legendary healing properties attributed to it, made it the perfect choice for an exclusive gift, also to promote diplomatic relations. As regards the production process, this was not governed by any official methodology, but production tended to follow secret family recipes that led to vinegars with different characteristics. However, the numerous customs passed down through the centuries in the areas of Modena and Reggio Emilia gradually converged into those types of vinegar which, from the 18th century, were normally termed “balsamic”.

Why “balsamic”?

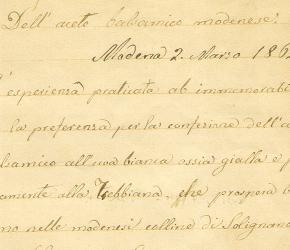

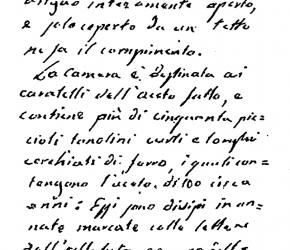

This adjective was intended to underline this particular vinegar’s medicinal properties and extraordinary characteristics. Merchants and traders were interested in the product and in 1605 a large supply was sent to the Venetian Republic. This was not, of course, the same product presented by the Duke on solemn occasions, but a vinegar which was greatly appreciated for use in the kitchen. Alongside the very finest product, intended to be passed down from one generation to the next as a precious gift, another version of the vinegar had been developed: while still excellent, this was less expensive to make and could be produced in far greater quantities. As it was sweet and still made from cooked grape must, it too was described as “balsamic”. The earliest surviving documented use of this term appears in the “Register of grape harvests and wine sales of the two secret Ducal cellars” (1747), which records the amount of product transferred to the ducal vinegar loft for the annual topping up. When the Napoleonic army arrived, the officers immediately realised the inestimable value of the vinegar stored in the Ducal cellars and promptly auctioned the barrels off as the spoils of war. In his commonplace book, ‘Zibaldone di un gastronomo modenese’, Carlo Vincenzi voiced his appreciation: “Modenese vinegar could revive the dead – and the Balsamic of the House of Este, which was adulterated with many other things in 1796, was unrivalled in terms of deliciousness and age”. On reclaiming possession of the Ducal Palace in 1814, Francesco IV, Duke of Modena, set about rebuilding his personal vinegar lofts, but the Restoration found a changed world, also regarding vinegar. The finest Balsamic was no longer the preserve of aristocratic families, as bourgeois families too, who had prospered, also proudly produced it. On visiting the Duchy of Modena in 1817, the Austrian chancellor, Prince Klemens von Metternich, expressed the desire to taste the «best» of that vinegar which the Duke had kindly gifted to the imperial Habsburg family on various occasions. In 1832, the medicinal properties attributed to Balsamic Vinegar were reiterated also by the famous composer, Gioacchino Rossini, in a letter sent to his Modenese friend, Angelo Catellani, Chapel Master of Modena Cathedral, thanking him for the vinegar received, which he confirmed to be «certainly refreshing and balsamic ». At the same time, economic and commercial requirements gave rise to attempts to increase output with drastically quicker production times, producing different types of “Modenese vinegars” made to recipes with various flavourings and wine vinegar. It is clear today that it was the natural product made with grape must which won preference, as can be inferred from the arrival in Nonantola, in 1839, of the renowned Italian agricultural scholar and pomologist, Count Giorgio Gallesio, for the purpose of visiting the vinegar lofts of his friend, the Count Salimbeni. His travel journals, today housed in Dumbarton Oak Library in Washington D.C., describe in minute detail the production processes of the two “Balsamic Vinegars”: one obtained with cooked grape must only, and the other with fermented must and must already turned into wine. Gallesio declares the first to be «sublime», and the second «also excellent », also describing the characteristics that set them apart from normal wine vinegar. In 1853, the new customs agreements stipulated with Austria and the Duchy of Parma included Balsamic Vinegar for the first time. The product was thus acknowledged as part of the country’s economic fabric, boosting business for producers of the more commercial variety of Balsamic, yet this did not overshadow Balsamic Vinegar of noble origins, made with cooked must only. The annexation of the Duchy of Modena to the Kingdom of Sardinia and later the Kingdom of Italy ensured the national and international renown of the Modenese elixir once and for all, and on 4th May 1860 the Ducal vinegar lofts were visited by the new sovereign, Victor Emmanuel II, King of Sardinia, and the Prime Minister, Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour. So impressed was the King by the Duke’s vinegar that it was decided that the best barrels would be transferred to the royal residence of Moncalieri Castle. At the time of the annexation to the Kingdom of Italy, the registers of the Ducal Palace of Modena listed eight different types of vinegar: fino, balsamico, semibalsamico, quasi balsamico, nostrano fino, nostrano ordinario, comune, agresto. (fine, balsamic, semi-balsamic, almost balsamic, fine local, ordinary local, common, unripe). This relocation also aroused the interest of oenologist Ottavio Ottavi, who wrote to the lawyer Francesco Aggazzotti requesting advice on the installation of a vinegar loft. The Count’s letter of reply in 1863 describes his family’s customary production practices in minute detail. This document, along with a letter to his friend Pio Fabriani (1862) would be used as the official recipe and basis for the Production Specifications of Traditional Balsamic Vinegar of Modena. During the Modena Agricultural Exhibition of 1863, some local noble families presented vinegars claimed to be centuries old. At the Paris World’s Fair in 1878, the French showed particular interest in Balsamic Vinegar. At the Emilian Exposition of 1888, Balsamic Vinegar was awarded a coveted medal.

The Consorteria

From the 1950s on, meanwhile, the movement of more and more families away from rural areas and into cities, made the production of Balsamic Vinegar problematic due to limited time and space available, and this noble tradition risked disappearing. Fortunately, in 1967, Rolando Simonini, a bank manager and sponsor of the local Fiera di San Giovanni festival in Spilamberto, organised a challenge between the best vinegars. It was named “Palio dell’Aceto Balsamico Naturale” (Natural Balsamic Vinegar Contest), and was so successful that in order to follow on from the event, which had seen around fifty producers compete, a guild named “Consorteria dell’Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale di Modena- Spilamberto” was established. In the years that followed, this guild of small producers succeeded in bringing about a revitalisation of the noble tradition of production at family level. Events organised by the Consorteria attracted the attention of numerous food and wine experts and journalists. In 1987, spurred into action by great interest from the market, the main producers, backed by the Chamber of Commerce and the Consorteria, obtained protection for the product registered as Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale di Modena D.O.C. (Traditional Balsamic Vinegar of ModenaControlled Designation of Origin) and the member producers took up the challenge to establish the product on national and international markets.. In a bid to set Traditional Balsamic Vinegar of Modena apart from the numerous other condiments available that are made using unregulated and uncertified procedures, the Chamber of Commerce asked the young automobile designer, Giorgetto Giugiaro, to design an exclusive bottle so distinctive as to symbolise and actually denote the brand of the precious product. This 100 ml bottle, bottled exclusively in plants authorised by the Italian Ministry of Agricultural, Food and Forestry Policies and closed with a special numbered seal, represents the only real guarantee of authenticity and quality, as established in the Production Specifications. In 2000, the product obtained European protection as Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale di Modena P.D.O. (Traditional Balsamic Vinegar of Modena Protected Designation of Origin), and in 2009 the Consorzio Tutela Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale di Modena was appointed to oversee the protection of the product.